Brian Fogg was brought up in Old Whittington and he has documented his life in Whittington in the 1930’s and 40’s. It is a very interesting account of the village and some of the people who lived there and I am grateful to Brian and his daughter Isabel for allowing this to be posted on the website.

Old Whittington Village

This section describes Whittington the way it was when I was young in the 1930’s and early 1940’s.

The major features and buildings I mention tend to have a significant meaning for me and within the descriptions are anecdotal remarks about why they have this significance.

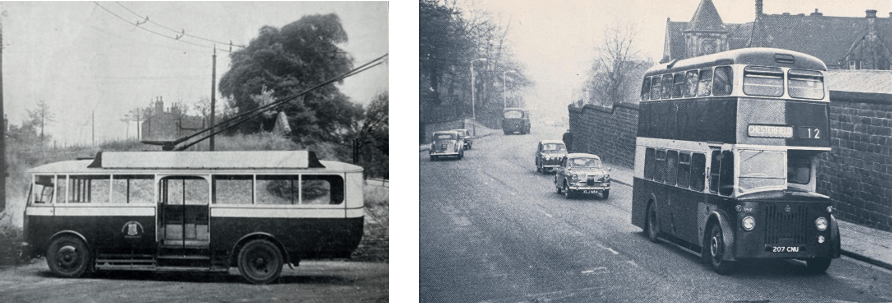

Whittington, which in the Domesday Book known as Witintune, is a fairly extensive village about 2.5 miles north of the market town of Chesterfield – a town probably best known for its church with the crooked spire. To reach Old Whittington you could travel along what is now known as the old Sheffield Road, but originally was the main road between Chesterfield and Sheffield. To reach Old Whittington from Chesterfield one could catch the green and cream

electric trolley bus to travel as far as Whittington Moor then a local bus which travelled from Whittington Moor to New Whittington via Old Whittington. Alternatively one could use the number 12 Sheffield white bus that travelled between Chesterfield and Sheffield. The bus passed through a place called Sheepbridge with a bus stop at the lower end of the Broomhill Park at the junction between William Street and Sheffield Road.

Electric trolley bus Number 12 bus in later years

Broomhill Park lies on a fairly steep hill with three parallel roads running across the hill; Holland Road being at the bottom of the hill, Prospect Road, the middle road, and Broomhill Road lying along the top of the hill, the latter was and still is the main link between Sheffield Road and Old Whittington village.

Streets, namely William, George, Victoria, Fowler, Rutland, Cavendish and Swanwick ran perpendicular to Broomhill Road: some running all the way down from Broomhill Road to Holland Road the others only as far as Prospect Road. At the far end of Prospect and Holland Roads was Whittington Hill, the steep main road leading from Whittington Moor along which the local bus ran to New Whittington.

This is a map of the general area covered by these writings.

- William Street/Prospect Road yard

- The fields beyond Leggett’s farm

- Fields next to Durham’s farm

- Whittington Hall

- The point where the photo of charabanc taken

- Slack Walk (marked by FP for footpath)

- Revolution House

- The Cock and Magpie

- Where the Church Hall was

- Brushes School

Alongside, and sloping upwards from Broomhill Road, are fields which belonged to a dairy farm owned by the Durham Family.

As a boy living in William Street I often had to take a jug up to the farm for a pint of milk costing 3 ha’pence. If I went around tea time the milk from the freshly milked cows would still be warm even though passing through a cooler; never pasteurised or homogenised in those days.

This was the farm with the milking shed at the lowest point of the picture

Durham Farm fields alongside Broomhill Road (3 on the map) stretched as far as a point opposite Cavendish Street past a small old quarry up to the boundary fence of a large white house situated some way up the hill from the road. Houses were built along the rest of the top side of Broomhill Road as far as the intersection with Whittington Hill and High Street, the main road through the village, but the approach to these houses was along a lane off to the left

of High Street. On the right hand side of Broomhill Road just beyond Swanwick Street was a haberdashery shop which I would have to go to for, perhaps, knitting needles for my Mother. It seemed to be owned by two nice elderly ladies.

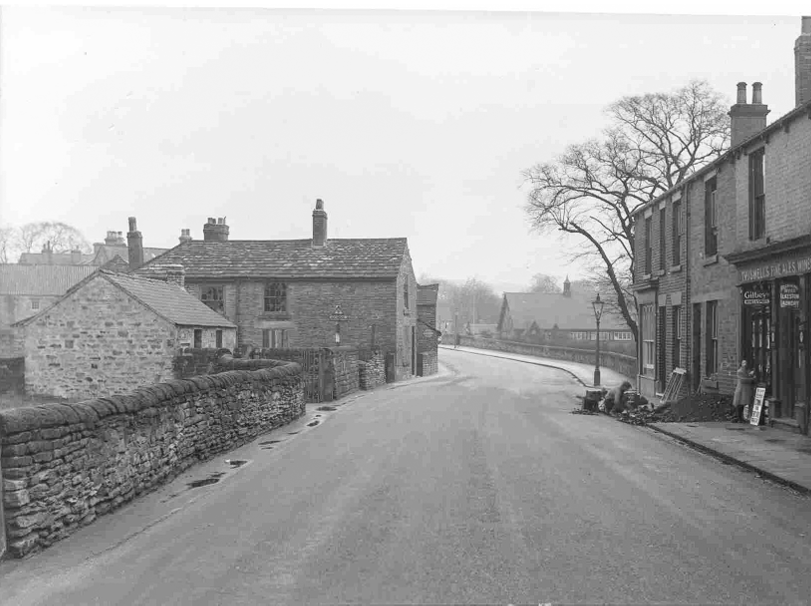

At the junction of Broomhill Road, Whittington Hill and High Street is the well known Bulls Head pub. On the right side of High Street going in the direction of New Whittington was a row of shops, the first being the Post Office. A little further on was a barbers shop owned by Mr Hardy, my barber.

This photo although years earlier shows the Post Office on the corner and the barber shop next to it.

Halfway along this row of shops I seem to remember a paper and confectionery shop and at the end of the row, at the junction with Station Road, was a family butchers. Beyond Station Road and further on along the same side of the road beyond a field was the Whittington Public Library.

Every weekend my mother sent me all the way from Prospect Road up Swanwick Street to order yet another joint of undercut beef. I often wondered why this couldn’t have been made a standing order to save the fairly long weekly walk.

The butcher’s shop was at the end of the row of shops shown here on the right. The library is visible in the distance.

The library was in the Swanwick Memorial Hall, a photo of which is shown below.

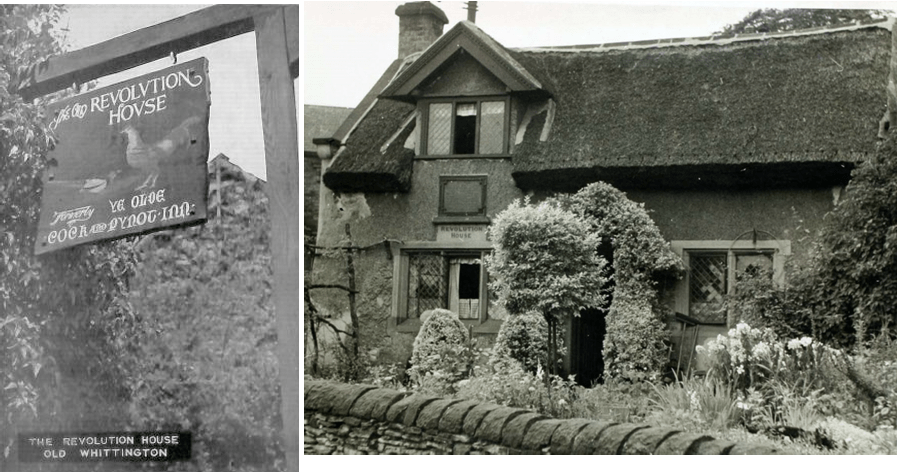

The Revolution House

A bit further along on the left hand side of High Street was, and still is, the famous Revolution House, previously known as the Cock and Pynot Inn. (Number 7 on the map.) This is famously the home of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 in which the Earl of Devonshire, his successor is now the Duke of Devonshire, and his co-conspirators plotted the downfall of James II, the last Catholic King of England, to be replaced by the protestant William of Orange and his wife Mary of England, daughter of James II.

I recall a function at the Revolution House in the 1930’s, probably the reopening of the house after its refurbishment by Chesterfield Council. Local dignitaries attended, together with the St Bartholomew’s church choir, of which I was then a boy member, and a local brass band. I remember we sang a hymn accompanied by the brass band which played so loud the choir was simply drowned out; anyway it was an exciting day for the choristers.

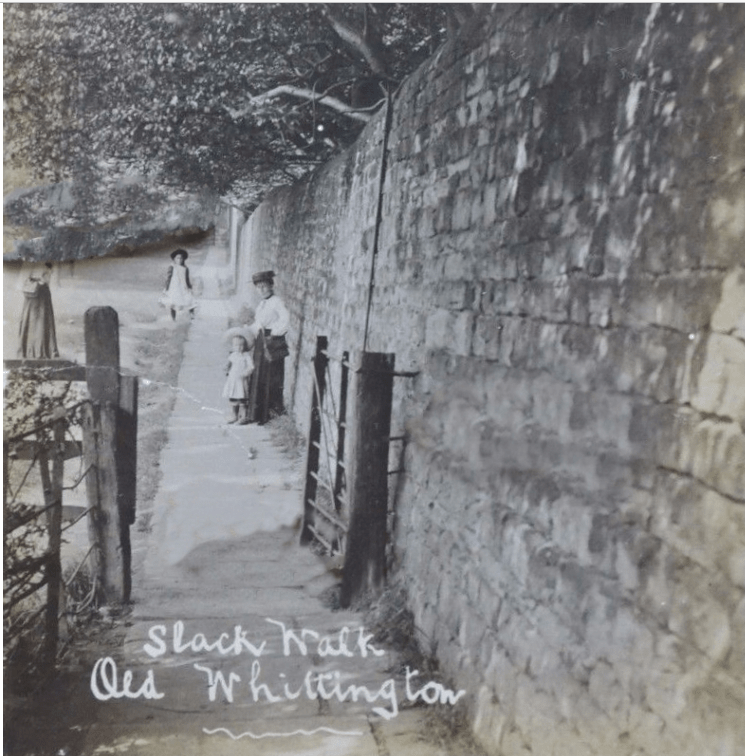

Cock and Magpie and the Slack Walk

Behind the Revolution House at the bottom end of Church Street North, is a pub called Cock and Magpie built in the 18th century (number 8 on the map). To the right of the pub is the Slack Walk, a shortcut to the church and which was convenient for the male members of the church choir; a few of the men would walk down to the pub after the Sunday evening service!

Often when walking to church for a service I would hear the 5 minute church bell start ringing when I was still at the bottom of the walk which meant I had to run like mad to get to the vestry, change into my cassock and surplice, collar and bow ready for the procession into the choir stalls. Heaven help any of the young probationers who had dared to pinch my collar and bow.

(These photos are very old, but probably closer to how the places looked than modern photographs.)

The Church Hall

Walking up Church Street North, leading off High Street you passed the Mary Swanwick School on the right and further along on the left was St Bartholomew’s Church Hall Sunday School (number 9 on the map). There was usually a weekend dance held at the hall and occasionally during the week a play would be performed by amateur actors.

The Church Hall before it was demolished.

St Bartholomew’s Church

Around the corner bearing right off Church Street was, and still is, St Bartholomew’s Church. Apparently a Norman Church had been on the site since 1141 but this was demolished in the 1860’s. A new church was built in 1866 but was damaged by fire in 1895; it was repaired and reopened in the following year. This is the church I attended in the 1930’s when I joined the choir as a probationer. I later became the main treble soloist. Soon after reaching this

position my parents started attending the church and my father also joined the choir.

The Church has a Lych Gate and to the right side of the path just through the gate were some graves or tombs dating from the 17th century; the epitaphs on the grave stones made fascinating reading. It was sad to see how young some of the people were dying in those days and how some of those buried there were young children and babies.

When I was a choirboy the Church was lit by gaslights, and it was frequently my task after the weekly choir practices to turn out the lights pew by pew after everyone had left. After the last one had been switched off, the church in the winter was obviously in pitch darkness, and that was when I would dash out of the church scared stiff hoping that none of the boys would be holding the door closed.

The beautiful old Rectory of the church was situated just outside the graveyard boundary wall and near the top of the Slack Walk. A path ran along the outside of the wall which led to a well known hill called Grass Croft. To the right of the path over a wooden fence was a field called the croft, on the other side was a boundary fence with a gate to the rectory garden. Many summer evenings the choir boys would play cricket on a very bumpy pitch in the middle of the croft; so bumpy I preferred to bowl rather than bat

The Swanwick Family

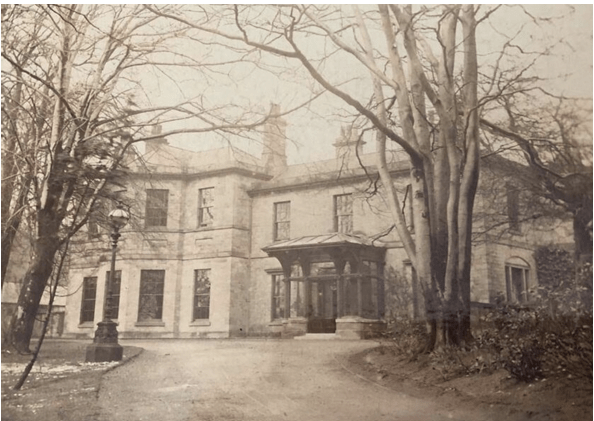

Continuing along the High Street, past the Revolution House and towards New Whittington, was Whittington House which could be reached by a long drive on the left side High Street, although the grounds of the large house extended to the other side of a stone wall running along the right side of the Slack walk.

This house, built in the early 1800’s, was owned from 1916 by the Swanwick family of Solicitors. The Mary Swanwick School was named after Mary, one of the daughters. On the way to church I often saw the locally well known solicitor Michael Swanwick who lived there.

Whittington House

I sometimes went to watch amateur Rugby Union matches at their ground in Stonegravels near Chesterfield and would see Michael Swanwick playing in the local team, although most of the team at that time seemed to consist of doctors, solicitors and other professional gentlemen.

Whittington Hall

Further along High Street on the left is the White Horse Inn, to which I refer later, and then further on the left, almost in New Whittington, was the entrance to Whittington Hall. (Number 4 on the map.) Apparently the Hall was built as a residence by someone called Henry Dixon in the early 1800’s but later became a hospital and then a care home for mentally deficient – or feeble minded – persons, as they were referred to by the government and others in authority. Initially this care home housed inmates of both sexes but later it

became exclusively for females. It seems that when I was aware of the Hall in the 1940’s it housed as many as 370 women and 30 staff.

In his book “The History of Whittington” the Rev. E. A. Crompton described the care home as one of the best organised in the country.

A departmental manager at the Company where I was serving my apprenticeship was aware that I had been fond of art when at school and asked if I would like to paint murals on one of the walls in the Hall

Whittington Hall

More Personal History of my Life in Old Whittington

I was born at 17 William Street North in Old Whittington in the front bedroom of my grandparent’s house. (Number 1 on the map.) Incidentally William Street is very close to Holland Road (which we called the bottom road) where, according to an item in the “Old Whittington One Place study” website, by Kev Walton, is where the local midwife Nurse Cheetham lived at No 42 Holland Road and, as 42 Holland Road is just a few stone throws from the house of my grandparents, I could have been one of the 5,000 or so babies she delivered around that time.

17 William Street is the house on the far left.

At the top of William Street, where it meets Broomhill Road and slightly to the left, is Broom House, a large house behind a high stone wall. The walls curve towards an opening and at each end of the opening, high stone pillars had been built beyond which was a long drive up towards the house. Living in this house was Mr Haslam, the Managing Director of the Sheepbridge Coal and Iron Company, which lay on the far side of Sheffield Road beyond the Iron bridge and towards Chesterfield. The bridge carried the main LMS railway line running

from Scotland down to London. Express trains thundering along the line stopped at Chesterfield Midland Station on its way down to London but slower local trains also stopped at Whittington Moor station. Just beyond the railway bridge was a road bridge under which passed River Whiting which had become over the years the colour of yellow ochre as industrial detritus was dumped as it passed the coal and iron works. Apparently it merged with River Rother as it reached Whittington Village.

Further to the left down Broomhill Road towards Sheffield Road and close to the road was Leggett’s Farm (number 2 on the map). Their field, which was accessed through a gate in the roadside wall, led either to the farm yard on the left or straight on past a copse of trees to a damp area called the Willows. As the name implies there were lots of willow trees and saplings. Beyond these trees was a hillock running parallel to the Willows. Further on was a path and stile that led to the bottom of one of Mr Durham’s fields which we used in the

winters for sledging; usually stopping just short of the stream which seemed to start at a duck pond near the farm yard and that passed through the Willows. The Willows ran alongside a rough field. At the end of this field nearest the farm was a small quarry and at the other end was a hill on which was an air shaft surrounded by a tall brick built round tower, which I presume provided ventilation for mining below ground. A hole in the brickwork near the

ground showed that the shaft was blocked by vegetation and that was where a family of foxes had a lair. Directly to the left of the farm and next to Broomhill Road was a sloping field that ran up to the fence by the railway line. In the summer time there was a profusion of large and glorious white flowers we called Penny Moons. Picking wild flowers wasn’t banned at that time so I often took a large bunch home to my Grandma or Mother.

I described this area at length because it played a big part in my childhood. I was friends with Frankie, the son of the Boam family who owned the farm. He had a sister called Winnie and together with the Carpenter children, referred to later, and sometimes others formed a friendly, but adventurous, gang. As a gang we used to play in the Willows and build dens out of the flexible willow saplings. We made fires and baked potatoes and boiled water to brew herb or even proper tea if any of

us could manage to steal tea leaves out of the caddy at home. In late autumn we were

allowed to fell a tree by chopping, not sawing. The bigger lads in the gang chopped the main trunk but after it crashed down we all lopped branches using hatchets we sneaked from home and dragged the lopped wood to a field near the quarry to make a huge bonfire. Even the trunk would be gradually chopped up and hauled to form the base of the fire. By bonfire night we had collected lots of rubbish including old newspapers to light the fire and the girls usually made a Guy Fawkes. November the fifth was very special but there were only a few fireworks; just a few rockets let off out of jam jars or bottles, a few little demons and the occasional Catherine wheel; hand held sparklers were cheap so these were always plentiful. Potatoes were baked in the fire when we could get near enough because of the heat. We would rake out these blackened objects but black skin and all were eaten, no worries about muck in those days. The fire embers would last for days so the activities around the remains of the fire continued for many nights.

In summer months and light nights we made small ovens in the wall of the quarry and with margarine or butter some of us pinched from home, together with an old pan that Frankie had obtained we somehow managed to make chips.

I had a walking stick made by my mother’s father for my Dad. It had a round head turned from spliced wood but one side of the head had come away leaving a head with a flat face which made a wonderful golf club of sorts. We struck a golf ball from the hillock in the Willows over the field to the tip containing the air shaft. It took about 3 or 4 strikes but it was fun. My Grandad bought me a cheap putter from Woolworth’s but my game was never the same.

Shops Around William Street

There were several corner shops around William Street. On the corner of Prospect Road and William Street North was a sweet shop, on the opposite corner was a small grocery shop owned by the Penistone family but later by the Booth family. At the top of William Street was Mrs Whittaker’s grocery shop.

This was my Grandmother’s favourite shop and where I was often sent to buy a pound of best butter or an ounce and half of barm, now referred to as yeast, for bread making.

On the corner at the junction of William Street and Holland Road was another general shop but we rarely used to shop there.

At the junction of Prospect Road and Sheffield Road was an off-licence, or beer-off as it was called at the time, with a good fish and chip shop next door. Out of my 3 ha’pence spending money I often bought a ha’p’orth of chips, with some fish bits thrown in.

My pals and I used to roller skate down William Street between Prospect Road and Holland Road and past the corner shop, across the road and round the corner onto Sheffield Road past the Gent’s toilet. There was very little traffic in those days so it was not too dangerous. Outside the shop was a slot machine where for a penny in the slot you could buy a Woodbine cigarette and two matches.

Where William Street meets Holland Road and Sheffield Road stood Sheepbridge Coal and Iron Companies Working Men’s Institute. It was a large brick building with its car park at the junction of William Street and Prospect Road and with its large gate on William Street.

There were very few cars using the car park at the time I was living in William Street,

especially during weekdays, so it made an excellent area for the lads of the region to play cricket or football. The Managers of the institute were Mr and Mrs Carpenter who had a daughter Winnie and a son, my age, called Ronnie, who was my friend.

Sheepbridge Institute

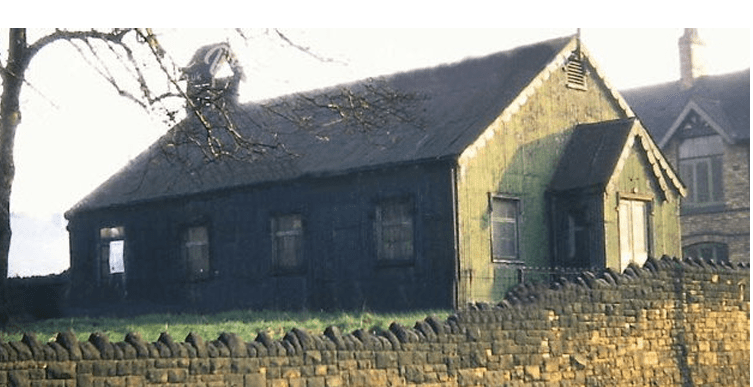

At the junction of Prospect Road and Sheffield Road and next to the Sheepbridge Institute was the “Tin Mission” Sunday School, so called because it was constructed entirely of corrugated steel and painted a browny red colour. It could be entered either from a gate on Prospect Road or through a gate on Sheffield Road next to the Institute and up some stone steps near the main entrance to the Mission Hall.

I still have a bible presented to me by the Reverend E. A. Crompton in 1937 for good attendance at the Sunday School. I remember very little of what I was taught; but it was fun every Sunday afternoon.

Tin mission in 1958

The influence Sheepbridge Coal and Iron Company had on the Surrounding Area

Sheepbridge Coal and Iron Company had blast furnaces used for making pig iron. Coke was used to smelt the iron ore to produce the molten iron after a blast of air is passed through the melt. Molten iron sinks to the bottom of the furnace but the remainder of the ore is left as a layer of white hot molten slag over the molten iron. At the end of each day the molten slag would be drained off into special tippable open railway wagons while the iron would be

poured into moulds to form iron ingots, called pig iron. The excitement began when the slag wagons were towed up a slag heap by what we called a Puffing Billy engine. When the still molten slag was tipped from the wagons onto the tip the whole sky would be dramatically lit up as the slag poured out of each wagon and down the slag heap slope; at least I thought it was dramatic but the other Broomhill Park folk might have had other thoughts, although not about climate change in those days.

Pouring the slag down the slag heap

Next to the slag heap and at the side of the Sheffield Road was a plant called the Cracker Factory where the cooled slag was broken (cracked) into small pieces to be covered in tar for road making or repair. Everything in the vicinity of the plant was covered in a white dust and the smell of tar.

The House at 17 William Street as I remember it

17 William Street was situated at the top right hand corner of a “yard” located at the junction of William Street and Prospect Road. The entrance to the yard was in William Street and number 17 was part of a row of “two up and two down” terraced houses situated up William Street towards Broomhill Road. Each two houses are separated by a ginnal (in Derbyshire it was pronounced jennal). The houses on the Prospect Road side of the yard were all “three up

and three down”. All houses had outside toilets, but because the “yard” was on a hill the back door of 17 William Street was reached from the yard level by two smallish flights of steps. Number 17’s toilet was halfway down these steps so going to the toilet in the winter was an unbelievably cold but necessary ordeal.

I keep mentioning the “yard” because in the early thirties, and later, houses were often built around ‘yards’ and this in effect produced communal centres. Ours certainly formed an essential communal and social group where everybody living around the yard knew everyone else’s business. However people were always available to help or just commiserate in times of trouble.

My Grandparent’s house was very basic. In the living room at the back of the house and facing the “yard” were all the facilities for living. The fireplace on the outside wall always contained a hot coal fire because it was where the kettle was placed on a swinging bracket, swung over the fire to boil. To the left of the fire grate was a built-in water “boiler” with a lid on which sat a ladling can used for filling and accessing the heated water. On the other side of the grate was an oven used mainly for baking loaves and cakes – usually on Friday

afternoon ready for the weekend. On the wall above the mantelpiece was a large portrait of William Gladstone. To the left of the fireplace were cupboards and in the wall around the corner was the door to the cellar where my Grandad’s tools and coal were kept. In the corner of the room to the right of the fireplace was a large round-bottomed boiler, which for some strange reason was called the “copper”. It was housed in a brick built surround and was heated from underneath by a small fire to which coal was fed through a small iron door. It was used on Monday wash days to boil the “whites” and provide water for

the wash tub. Next to the “copper” was a large deep sink with just a cold water tap, hot water for doing the pots was ladled from the fireplace boiler. A gas cooker with oven and a large mangle with worn wooden rollers were beyond the sink and next to the back door leading to steps down to the “yard”. On the wall at right angles to the back wall was a sideboard on which stood an accumulator (battery) operated radio which also had an eliminator – which presumably reduced background noise and hissing. In the middle of the living room was a

pinewood table used for all manner of things but mainly eating, game playing and, more importantly, household chores like baking and ironing.

In the wall opposite the back wall was a door which led to the stairs up to the bedrooms or through to the front room, called the parlour if you were posh; today it would be called either the sitting room or the lounge. Whatever it was called it was only used on Sundays or special days like Christmas. It had a small fireplace on the same side as that in the living room and an upright piano against the wall next to the stairs. There was a sash window on the front

wall and an outside door which opened, via a donkey stoned step, through a small front garden onto William Street. I would often see my Grandma sitting on the window sills outside the upstairs and downstairs windows with her legs through the slightly open sash windows cleaning the outsides of the window panes, she apparently had no fear of heights. The front garden had a removable grate through which the coal delivery man emptied his sack into the cellar, if it was in small lumps called “slack”. If in large lumps it was dumped into the street and “got in” by carrying bucket by bucket to the open grate. Also in the front garden was a small flowering lilac tree which always smelled lovely when in blossom. Up the steep stairs between the back and front rooms were two bedrooms – no bathrooms or en suites in those days.

How We Lived in the Early Thirties

My Grandma seemed to run the house around an arduous weekly routine but always making sure my Grandad’s needs were taken care of, I suppose because he was the breadwinner doing a heavy job as a blacksmith at a local wagon and carriage works. Monday was always wash day. She got up early to light the copper fire, making sure the main fire was well stacked up. She then made sandwiches for my grandad’s lunch, mashed his tea and filled his can before

packing them into his wicker lunch basket; all this after cooking his breakfast. It was usually seven o’clock when he left to catch the bus to work in New Whittington.

On Monday evenings after cooking the evening meal, clearing up and washing the “pots”, the pinewood table would be partly covered with a blanket and used to iron the day’s washing. Two cast iron smoothing irons were in use, one being heated by the fire whilst the other was in use for ironing. I can still smell the clean ironed clothes that had been dried outside in the yard. In the winter they would often be frozen stiff as a board while drying.

A couple of evenings a week my Grandad would probably walk down to the Red Lion pub in Whittington Moor for a pint or two of best bitter – probably to get away from the ironing chore but mainly to rehydrate after the heavy hot work of the day. On the other hand he loved his pint or two of beer. On other evenings after the evening meal my Grandad would often prepare to repair a family member’s pair of shoes or boots. Out would come the cast iron “last” attached to a heavy piece of wood which, when held between his knees was long

enough to bring the “last” to working height when he sat in his favourite chair next to the gas stove. He would sharpen his cobbling knife first using his leather strop and finally stroke the knife over his bald patch to fine finish the sharpening process. As a child I always watched the final procedure with bated breath feeling he might accidentally slice his head. Once he had placed the shoe on the “last” and nailed the leather to the sole or heel of the shoe he

would shape the leather around the sole or heel using the knife which cut the leather as though it was butter. After hammering the final nails into the shoe he would use a rasp to clean up the profile ready for applying the heel ball wax. He would heat up the heel balling iron on the gas cooker and then melt the stick of wax with the hot iron to seal the cut surface of the leather. The smell of melted heel ball wax was lovely.

On the evenings he went to the Red Lion, my Grandma would make sure supper was ready for Grandad when he returned. She would open a bottle of Whitbread’s pale ale ready for his return, have his favourite cheeses in the lidded cheese dish together with a peeled raw onion and a chunk of home made bread. The Sheffield Star newspaper was usually spread out on the table under the food ready for him to read.

Friday was always bread making day ready for the weekend. I was fascinated watching my grandma make bread. Her pancheon on the kitchen table was filled with flour, the middle of the flour hollowed out into which water was poured and the yeast added and around the rim of the hollow a sprinkling of salt. After a few minutes my Grandma, who was very small, but could just reach the contents of the pancheon, scraped the flour from the rim of the hollow

into the water then she would mix and pound the dough until it became ready to be left to rise.

This seemed to be helped by placing the pancheon with its dough into the warm fireplace and covering it with a tea towel. The risen dough was cut up and put into the well used baking tins and then into the hot oven. That’s when the whole house was filled with the glorious smell of baking bread.

I also have to mention that Friday night was bath night. A small oval shaped tin bath was brought up from the cellar and placed on the rug in front of the hot fire. It was filled from the fireplace boiler using the ladling can and then water ladled from the cold tap to adjust the temperature until bearable to one’s bottom. I’ve just remembered that before going over to my Aunt Eliza’s house across the yard my Grandma would put on the wireless so that I could

listen to the Friday evening play which were often terrifying thrillers; I remember listening to “Gaslight”, “Rocking Horse Winner” and “Mary Rose”. They all put the fear of god into me but I couldn’t get out and shut down the wireless. In addition the fire being very hot heated the side of the bath to the point where I had to sit away from that side. I came out very clean but boiled.

In addition to the scary plays on Friday evenings, the wireless in the living room played a big part in our lives in William Street. First of all my Grandad loved boxing, probably because as a young man he would accept the challenge of a boxing professional who, at the Nottingham Goose Fair, offered a fiver to anyone who could stay in the ring for a couple of rounds. Grandad would get up at 3am at night to listen to commentaries on fights by Joe Louis, Max Schemling, Max Baer and others from America. Woe betide us if the accumulators hadn’t been charged at the time.

What We Ate in the 30’s

My Grandad was by no means rich but we always ate very well. Monday being washday meant that bubble and squeak was the main meal. This was convenient because food was left over from the previous weekend. Other days we would probably have liver and onions, steak and chips, rabbit stew and at least once a week we would have herrings or bloaters, the latter being a gently smoked herring, or kippers, grilled over the open fire; I can hear and smell the

noise of cooking now. The herrings and bloaters were unfilleted so they contained the roe, which if “hard roe” was delicious, but no one wanted the roe if soft. I never knew where Grandma bought the food.

If we had toast as part of a meal I was allowed, as I got older, to sit in front of the fire holding slices of bread on a toasting fork held up to the hot coals and toast both sides of the bread under the watchful eye of Grandma.

Weekend meals were always my favourite. Most Saturdays my Grandparents would go on the bus to Chesterfield, first to the pork butchers to buy a warm pork pie, possibly a ham hock and some tomato sausages which we all loved. They would then cross to the Market where they would buy a joint for Sunday lunch, vegetables, usually with mushrooms and salad items, and often mussels; all of which were at cut price because it was approaching market closing time.

On Saturday Grandma would boil the mussels in a bucket on the gas stove. She would then remove the mussels from the shells and soak in vinegar with pepper in a large dish. My sisters would be invited for tea to eat the mussels with chunks of buttered homemade bread. As a treat we would have marshmallow coconut covered buns from the shop across the road.

Sunday was best because we always had a cooked breakfast of eggs and bacon, sausages, mushrooms and tomatoes with fried bread followed by toast and jam. Later the roast of the day, which could be either beef, lamb or pork, never chicken, would go into the gas oven. If lamb, the new potatoes would be scraped and peas podded ready for boiling. The fresh mint would be finely chopped ready to make the sauce; this was always my favourite roast meal. If

it was beef, the potatoes would be roast and basted round the roasting beef bit. We also had Yorkshire puddings. When it was pork, my Grandma always made sure it had lovely crackling and plenty of apple sauce. Whatever the roast the gravy was always rich and tasty – without lumps – as was the custard with the pudding.

Tea was often ham cut from the roasted or boiled hock bought on Saturday, accompanied with salad. After the long walks on summer Sunday evenings, described below, the air was usually still warm so we would sit on the steps outside the back door and eat slices of bread and dripping fresh from the day’s roasting pan. I liked lots of salt on my bread and dripping. My sisters and I always demanded the tasty brown part of the dripping that settled at the bottom of the dish.

In addition to all of this wholesome food we had our share of ice cream. Mr Hardy would come to our street in the summer in his horse and cart and sell us delicious top quality white ice cream. Also Palings would come a little later along Sheffield Road and up Broomhill Road, stopping at the top end of William Street and sell a yellow creamier ice cream with more generous helpings for the same price as Mr Hardy’s. I seem to remember they were both a ha’penny a cornet. Alternatively, we could go to the corner shop and buy a triangular bar of Wall’s frozen fruit flavoured water for a penny or if we were “hard-up” they would cut the bar into two and sell a piece for a ha’penny. At the same shop we could also buy five Stockwell cream of cream caramels for the same price. Happy days.

The White Horse Inn

On other Sunday evenings the whole family would walk up through the fields to New Whittington, and call in at the White Horse Inn. We children would have crisps and a drink of lemonade whilst the men drank beer and the ladies the odd gin and tonic. On other occasions we would walk to Brearley Park to gather around the band stand to listen to the brass band – if we got bored we would go and play on the swings. We would finally all walk back home again. Sundays were usually idyllic. Incidentally the park was named after, and donated by, the man who invented stainless steel in Sheffield and lived for a while in New

Whittington.

Brearley Park

My dad initially served an apprenticeship as an engineering fitter and attended night school, however he somehow found time to learn to play the violin. He gave up the idea of becoming a fitter and became a professional violinist playing in the Chesterfield Symphony Orchestra later becoming musical director of a large cinema orchestra in Sheffield.

On 26th January 1928, the Kinematograph reported that:

“J. Fogg, who comes from Chesterfield, has been appointed musical director at the Tinsley Picture Palace, Sheffield. Mr Fogg has an entirely new orchestra under his control.”

At some point my Dad informed us that he was going to sing on the wireless, from Sheffield I think, and on this special day we all congregated in the front room of 17 William Street, gathered around my Grandad’s crystal set in the front room. My Grandad tickled the crystal with the “cat’s whisker” until he found the station. We then shared the headphones and each heard snippets of my Dad’s voice. But when the cinema organ became popular there was no longer a need for an orchestra and his full time musical profession came to an end. He did, however, subsequently form a dance orchestra with Mr Daykin, a friend who also lived in William Street in the top “yard”. In addition to the violin he learned to play the saxophone and the harmonica.

The Church Choir

I am not sure how old I was when I first heard of the church choir. I was in William Street when I saw a pal walking up towards Broomhill Road in a hurry. I asked in our local dialect “wee’re tha gooin Ron” and he said “a’m gooin’ t’ choir” I said “what’s tha mean choir” he said “tha’ knows at church where we sing, a’tha cumin” I said yes and that was my introduction to the St Bartholomew’s Church choir. I would never have spoken like that in

front of my parents. They spoke “proper” I suppose.

The quickest way to the Church from William Street was up through Durham’s field off Broomhill Road then through a field where we used to fly our home made kites (until one day Mr Durham came and cut all of our kite strings with a penknife). We continued across a field where we used to sledge and finally through a couple of fields and a path that came out on Church Street opposite the Mary Swanwick School. A short walk up Church Street and round

to the right and we were at the Church.

From the top of the first field (below) you can see the path from the stile on Broomhill Road and also a lovely view of Broomhill Park over to the Sheepbridge Works slag heaps.

Photograph taken outside the old rectory

In a photograph of the choir, which I am informed is still on a wall in the church, I am the fourth from the left on the front row and my Dad is third from the left on the back row, almost directly above me.

World War 2 Experience

We were still at war with Germany at this time. We had a small garden and so the usual Anderson air raid shelter was delivered in parts. It was necessary to dig a large hole in the garden to the prescribed dimensions. I think my neighbour’s son and I assembled the shelter in the hole and informed the authorities who came along and covered the floor and sides of the shelter up to ground level with concrete. The soil from the hole was used to cover the

shelter, supposedly making it safe to use in the event of an air raid. We also built steps from the entrance down to the floor of the shelter. However during heavy rain the shelter had water a foot deep. It remained like that until the shelter was removed after the end of the war.

Our other neighbour, Mr Pratt, decided to make the space under his house warm and comfortable with mattresses and blankets. We were invited to share the space with his family in the event of an air raid alarm which became necessary once the bombers were hitting Sheffield, Manchester and Liverpool. We could hear the throbbing drones of the Heinkel bombers as they came up from the South and directly over Chesterfield. Once they got beyond where we lived we started to hear the thuds of the bombs hitting Sheffield. Some of us were out from under the house looking at the flashes of the exploding bombs, but of course no lights were allowed. On one occasion a bomber returning from a raid crashed into Brierley Woods where we used to play and it was not much later that we found the crashed bomber in a field next to the woods.

It never occurred to us that if our houses were hit by a bomb we would be buried under or even killed by the masonry of the house.

It was rumoured that a returning German bomber strafed workers walking to work early one morning as they passed Whittington Moor railway station. There had been a lot of activity over Sheffield the night before. As lads we went to look for shell holes in the walls around the bridge near the station, as well as for pieces of shrapnel, but found nothing, so it’s still a mysterious rumour; shucks! That was Whittington’s war experience – I think.

My Education

I attended the Brushes County Primary School when I was 5 years old. I remember sitting next to a little girl called Nellie Rich who made me laugh a lot. It was a happy time for most of us except when so-called naughty boys, me included on a few occasions, were sent to the office of the headmistress Miss Rollinson for the cane as punishment for misdemeanours (often six strokes across the hands) – probably deserved. We couldn’t tell our parents.

For various reasons I failed my 11 plus examination. However before my Dad (known as young Jim or just Jimmy) died, he presumably pre-empted my fascination with girls and decided that instead of attending the “Mary Swanwick Secondary Modern School for boys and girls” I should go to the “Peter Webster Secondary Modern School for Boys” situated in

Whittington Moor about 2 miles, or a penny bus ride away. Maybe the actual decision was based on the fact that the latter school had a better academic record. They were happy times at this school. I seemed to enjoy Mr Gasson’s maths classes and was encouraged to do art in a class run by Mr Arthur Green. Time in the gym and playing cricket were great but times in the workshop learning woodwork and metalwork were more exciting – these activities

seemed to be in my blood, which is not surprising because of my Grandad’s occupation as a blacksmith, my maternal Grandad ran a woodworking business; and my father served an engineering fitters apprenticeship before becoming a violinist. Incidentally I never knew how he came to be a violinist of professional status.

Every Monday morning my form master, another Mr Green, had to go and supervise the collection of National Savings and would always leave me or another “good” boy in front of the class to write down on the blackboard the names of those who misbehaved during his absence. The only boys who misbehaved were the class bullies and so no one dared write their names on the board. When Mr Green returned he never believed the board could be empty so we all got a stroke of his cane across the bottom just in case.

Our head master, Mr Jim Middleton, had a brother Tom Middleton who was the chief Accountant in the local Osram factory making lamp bases. Mr Tom asked his brother if he could send along 3 or 4 likely lads to be interviewed for the post of apprentice draughtsman. Fortunately I was successful in obtaining the post and started work on the 21st December at the age of 14 years for the great wage of 14/6d a week, working from 7.30am to 5.30pm Monday to Thursday and 7.30am to 6.00pm on Friday and then Saturday mornings. It was hard but I loved the work.

I had not even thought about my future technical education or whether such a thing was possible, but then, as with joining a choir, serendipity played its part again through Jack Cheetham. He was older than me but was still an apprentice fitter in the same company. As I walked past his workbench one day he said he was going to enrol at the tech that evening. I said what’s tech mean and he said it was the college where you learn engineering and he asked whether I would like to go with him. I arranged to meet him at the Whittington Moor

trolley bus terminus. I enrolled in the pre-senior stage of the Ordinary National Course at the Chesterfield College of Technology and it only cost about 5 shillings for the year. I somehow passed the year and got to the end of the ON course and into the Higher National Course which involved attending three evening classes a week and one day release from work. I passed the HNC with distinctions and was asked whether I would like to study for a London

University External Degree. I had no idea what this meant but I said yes. It involved Matriculating in less than one year doing pure and applied maths, Euclidean geometry, physics, chemistry, French and English. Myself and a few of my colleagues from the previous course passed in one attempt and moved on to the one year intermediate course and then the two year BSc degree course. To do this required me to attend five evenings a week and Saturday morning, in addition to time at home to write up project and lab reports. My lecturers Mr Whittaker and Mr Miles became my role models. Anyway thanks to the skill

and patience of our lecturers, after all this hard work I managed to obtain an honours degree in mechanical engineering.

I was promoted soon after the end of my apprenticeship to development designer working on the design of new processing machines and in particular a large transfer press involving technical innovations of which I am proud to this day. I also became interested in plasticity in metal forming because the products of the company I worked for involved forming processes.

My first published paper in the “Engineering Journal” audaciously criticised the work of Professor Swift at Sheffield University. He invited me over as a twenty something engineer to meet him and his research colleagues to discuss the problems of deep drawing of sheet metal components; I found out that Professor Swift was an external examiner on the London University Degree course I was still taking.

I was encouraged to apply for the post of Assistant lecturer at the Chesterfield College of Technology. I was successful and was able to start my research on metal forming plasticity and register for a PhD at London Imperial College. However it was difficult to teach 23 hours a week and do research at Chesterfield and I was advised by my teaching colleagues to apply

to a research oriented college, which happened to be the Royal Technical College Salford. After initial disappointments I was finally able, with the support of Professor Chisholm our head of Department, to develop a metal forming laboratory which was reputedly one of the finest in Europe. I was able to continue my research but it was also necessary to supervise my

PhD students at the cost of obtaining my own PhD. Even so, I managed to publish a number of papers on my main subject and others. After early retirement in 1984 I was offered the post of Visiting Professor in the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA. It just shows that being deprived of a University education but starting an apprenticeship at the age of 14

does not mean you cannot achieve academic status, albeit with a lot of dedicated hard work.