The following account and information kindly provided by Chris Cooke from personal family history records.

The Glasshouse Pits Tragedy of 1865

Daniel Cooke was born in Staveley in about 1849. He was the eldest son of Vincent and Emma (nee Needham) Cooke. At the 1861 Census, the family were living at Apperknowle and Daniel, although only 12 years old, was already working as an ironstone miner, probably at the same mine as his father, Vincent.

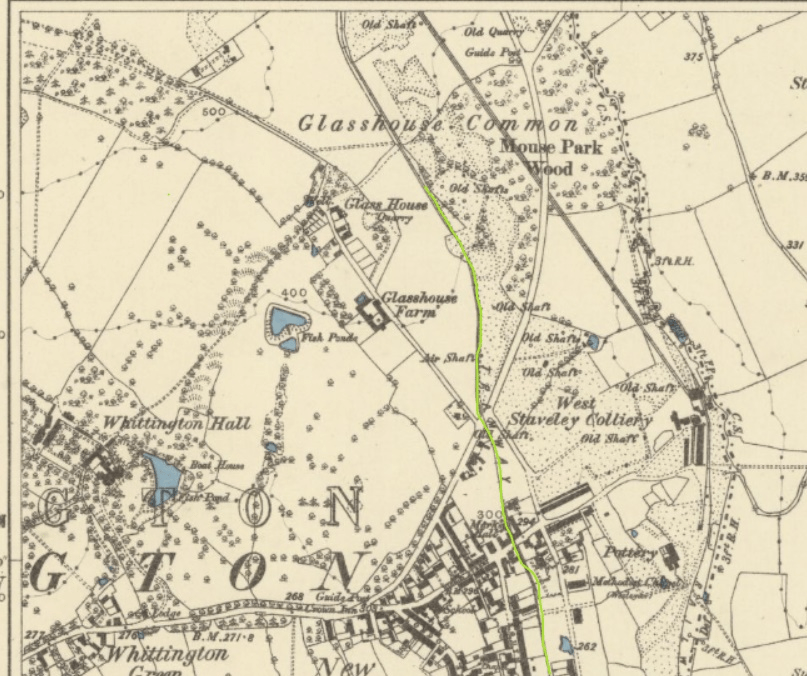

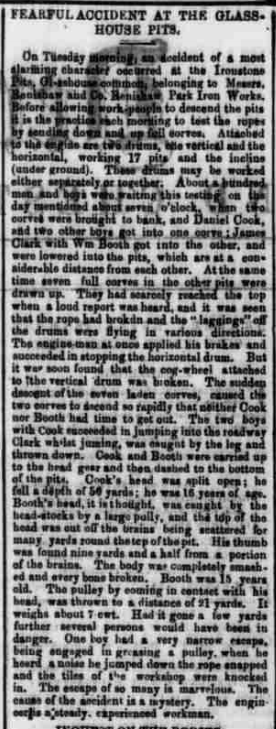

As recorded in The Derbyshire Times of Saturday, 12 August 1865 after 15-year old Daniel arrived for work on the morning of 8 August, an accident of a most alarming character’ occurred at the Ironstone Pits on Glasshouse Common at Whittington, belonging to Messrs Renishaw & Co, Renishaw Park Iron Works.

Daniel had waited, along with around 100 other men and boys, for the daily test on the ropes, which was done by sending down and up full corves (tubs or baskets). When the test was complete, at about 7 o’clock, Daniel Cooke, along with two other boys, got into one of the corves; James Clark and William Booth (also 15 years old) got into another, and they were lowered into two of the pits. At the same time, seven full corves were drawn up from the other pits. The full corves had scarcely reached the top when ‘a loud report was heard’ and it was seen that the rope had broken, and that the ‘laggings’ off the winding drums were flying in various directions.

The engine-man applied his brakes and succeeded in stopping one of the drums, but the cog wheel attached to the other drum was broken. The sudden descent of the seven full corves caused the other two corves to ascend so rapidly that neither Daniel Cooke nor William Booth had time to get out. The other two boys with Daniel managed to jump out. James Clark also managed to jump but was ‘caught by the leg and thrown down’. Daniel and William were ‘carried up to the head gear and then dashed to the bottom of the pits’.

The Derbyshire Times reporter did not spare his readers the gory detail – Daniel’s head was split open as he fell a distance of 56 yards down the shaft. Poor William’s head, it is thought, was caught by a large pulley on the head stock and ‘the top of his head was cut off, the brains being scattered for many yards around the top of the pit’. His ‘body was completely smashed and every bone broken’. The pulley, which weighed around 7 hundred-weight (about 400 kg), was thrown a distance of 21 yards.

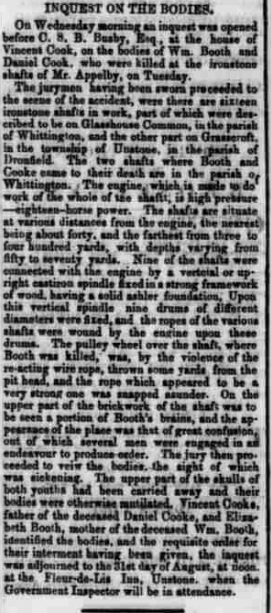

The initial inquest was held the following day – remarkably, this was at the house of Daniel’s father, Vincent Cooke, and the jury convened there. After a visit to the scene of the accident, the jury also viewed the bodies, ‘the sight of which was sickening. The upper part of their skulls had been carried away, and their bodies were otherwise mutilated’. For Vincent Cooke and Elizabeth Booth, called upon to identify their sons’ bodies, it must have been nothing short of completely horrific. The inquest was adjourned, to be re-convened at the Fleur-de-Lys Inn at Unstone, when the Government Inspector could also attend.

As recorded in The Derbyshire Courier of 2 September 1865 (attached, see column 3), at the reconvened inquest held on 30 and 31 August, the jury concluded that the accident had been caused by insufficient management, in that sixteen different shafts had been worked from the same engine, and that this was recognised as unsafe practice.

The Derbyshire Times of 23 December, 1865 (attached, see column 4) carried a report on “Important Government Prosecution Against Messrs Appleby and Company Renishaw” who were the owners of the mine. They were charged by the Government with five breaches of the Government Regulations for the conduct of mines, etc. It would appear the charges were primarily related to technical aspects of the mines’ operation over a period of time, but one specific charge of “not establishing special rules at a pit at Whittington on 8th August” is presumably directly linked to the inadequate operations that led to Daniel and William being killed that day. Vincent Cooke (presumably Daniel’s father) appeared as a witness for the prosecution. Whilst other witnesses were called by the defence it is reported that, under cross-examination, ‘the facts spoken to by Vincent Cooke were admitted’.

Excerpt below from Derbyshire Times August 12 1865:

The 1883 map shows roughly where the colliery would be and the tramway which was built to take the coal from Grasscroft, Hundall and West Staveley collieries down to the railway line at the bottom of the village.